Critical Care Survival Guide: An Overview

Navigating the intensive landscape demands vigilance; understanding HIV, glucose infusions, and diverse penile anatomy alongside ethical considerations is paramount for optimal patient outcomes.

Understanding the Critical Care Environment

The critical care unit (CCU) is a high-intensity setting demanding rapid assessment and intervention. Diverse patient presentations, from HIV infection management to those requiring glucose infusions, necessitate a multidisciplinary approach. Awareness of anatomical variations – even considering diverse penile anatomy – fosters holistic care. Ethical dilemmas, like end-of-life decisions, are frequent. Constant vigilance regarding infection control, alongside understanding fluid balance and neurological monitoring, is crucial for survival within this complex, dynamic environment.

Common Critical Illnesses

Critical illness encompasses a broad spectrum, demanding swift recognition and tailored treatment. Conditions like sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and acute kidney injury (AKI) frequently require intensive support. Managing HIV infection, alongside addressing metabolic imbalances like those requiring glucose infusions, is vital. Understanding diverse presentations – even acknowledging anatomical variations – aids diagnosis. Ethical considerations surrounding end-of-life care are often present, necessitating compassionate and informed decision-making.

Monitoring Vital Signs in Critical Care

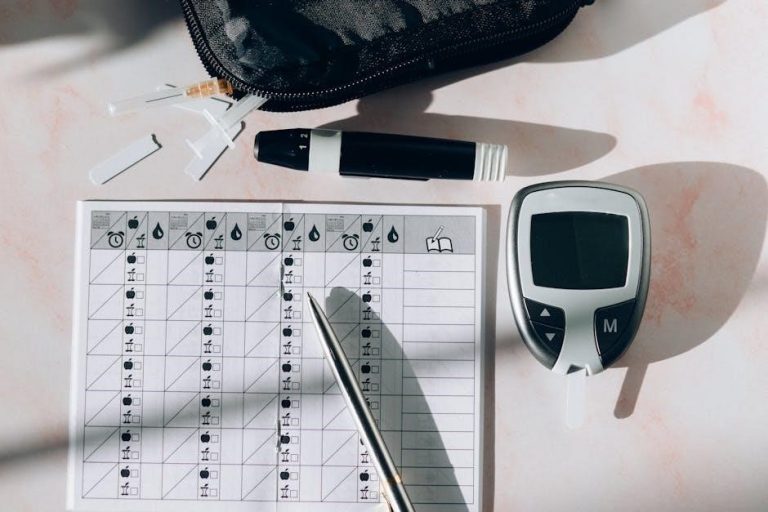

Continuous assessment of heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and temperature is crucial; vigilance alongside glucose monitoring ensures timely intervention and improved outcomes.

Heart Rate and Rhythm Monitoring

Precise cardiac monitoring is fundamental in critical care, utilizing ECG to detect arrhythmias like tachycardia or bradycardia. Continuous observation allows for swift intervention, potentially averting life-threatening events.

Understanding the underlying cause – electrolyte imbalances, hypoxia, or medication effects – is vital. Prompt recognition and treatment, alongside glucose level checks, are essential for stabilizing the patient.

Regular assessment, coupled with a grasp of diverse anatomical variations, contributes to effective cardiac care and improved survival rates within the intensive setting.

Blood Pressure Management

Maintaining adequate blood pressure is crucial, often requiring vasopressors or intravenous fluids. Hypotension can stem from sepsis, hemorrhage, or cardiac dysfunction, demanding rapid diagnosis and intervention.

Continuous arterial line monitoring provides real-time data for precise titration of medications, ensuring optimal perfusion to vital organs. Consideration of anatomical diversity and glucose levels is key.

Careful assessment, alongside awareness of potential complications like arrhythmias, guides effective blood pressure control and enhances patient stability in the critical care environment.

Respiratory Rate and Oxygen Saturation

Monitoring respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are fundamental to assessing ventilation and oxygenation. Tachypnea or hypoxemia signal potential respiratory distress, requiring immediate attention.

Pulse oximetry provides continuous, non-invasive saturation readings, while arterial blood gas analysis offers a comprehensive evaluation of gas exchange. Diverse anatomical considerations are vital.

Interventions may include supplemental oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, or intubation, guided by clinical assessment and physiological parameters, ensuring adequate respiratory support.

Temperature Regulation

Maintaining normothermia is crucial in critical care, as both hyperthermia and hypothermia can exacerbate illness and impair organ function. Continuous temperature monitoring is essential.

Active cooling measures, such as cooling blankets or antipyretics, address fever, while warming strategies—like warm fluids or blankets—combat hypothermia.

Understanding diverse anatomical variations and considering glucose infusions alongside temperature control are vital for optimal patient stability and recovery within the intensive environment.

Airway Management Techniques

Securing a patent airway is paramount; utilizing NIV, intubation, and mechanical ventilation, alongside anatomical awareness, ensures adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV)

NIV offers respiratory support without intubation, utilizing masks to deliver positive pressure. It’s crucial for conditions like COPD exacerbations and heart failure, reducing work of breathing and improving oxygenation.

Careful monitoring of respiratory rate, tidal volume, and patient comfort is essential. Contraindications include severe facial trauma or inability to protect the airway.

Proper mask fit and synchronization with the patient’s efforts maximize effectiveness, minimizing complications like aspiration or skin breakdown.

Endotracheal Intubation

Endotracheal intubation secures the airway with a tube inserted into the trachea, enabling mechanical ventilation. Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is often employed in emergencies, prioritizing airway control.

Confirmation of correct tube placement is vital – utilizing auscultation, end-tidal CO2 monitoring, and chest X-ray. Potential complications include esophageal intubation, vocal cord injury, and aspiration.

Continuous monitoring of vital signs and meticulous cuff pressure management are crucial post-intubation to prevent complications and ensure effective ventilation.

Mechanical Ventilation Basics

Mechanical ventilation supports or replaces spontaneous breathing, delivering tidal volumes and adjusting respiratory rates. Common modes include volume control (VC) and pressure control (PC) ventilation, each with distinct advantages.

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) improves oxygenation by preventing alveolar collapse. Careful titration of ventilator settings is essential to avoid ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).

Regular assessment of respiratory mechanics, arterial blood gases, and patient comfort guides ventilator management, aiming for optimal oxygenation and ventilation.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Maintaining homeostasis requires careful intravenous fluid administration, monitoring sodium, potassium, and calcium levels, and assessing overall fluid status diligently.

Intravenous Fluid Administration

Careful fluid resuscitation is crucial in critical care, demanding precise assessment of patient volume status and appropriate fluid selection. Isotonic crystalloids, like normal saline, are frequently initial choices, but lactated Ringer’s solution offers buffering capacity.

Monitoring response to fluids—via central venous pressure (CVP) or other dynamic indicators—guides further administration.

Always verify glucose sources before initiating infusions, as noted in pharmaceutical guidelines, to prevent metabolic disturbances.

Electrolyte Imbalances: Sodium, Potassium, Calcium

Maintaining electrolyte homeostasis is vital in critically ill patients. Hyponatremia or hypernatremia requires careful correction, guided by serum sodium levels and neurological status. Potassium imbalances—hypokalemia or hyperkalemia—can induce arrhythmias, necessitating prompt intervention.

Calcium derangements impact neuromuscular function and cardiac contractility.

Regular monitoring and timely supplementation, considering glucose infusion interactions, are essential for optimal patient stability.

Monitoring Fluid Status

Accurate fluid status assessment is crucial, employing clinical indicators like urine output, central venous pressure (CVP), and pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) data when indicated.

Daily weights provide valuable trends, while assessing for edema and capillary refill aids in evaluating perfusion.

Consider glucose’s influence on fluid shifts and tailor intravenous fluid administration accordingly, preventing both hypovolemia and overload.

Medication Administration in Critical Care

Vasopressors, sedatives, antibiotics, and glucose require precise titration and vigilant monitoring to optimize hemodynamic stability and combat infection effectively.

Vasopressors and Inotropes

Vasopressors, like norepinephrine and dopamine, elevate blood pressure by constricting peripheral vessels, crucial in distributive shock. Inotropes, such as dobutamine, enhance cardiac contractility, improving output in cardiogenic shock.

Careful titration guided by arterial lines and hemodynamic monitoring is essential.

Potential adverse effects include arrhythmias and tissue ischemia, necessitating continuous assessment.

Glucose infusions must be verified before administering these medications, ensuring metabolic stability alongside circulatory support.

Sedatives and Analgesics

Sedatives, like propofol and benzodiazepines, reduce anxiety and facilitate mechanical ventilation, but require careful monitoring for respiratory depression. Analgesics, including opioids and non-opioids, manage pain, a common source of distress.

Daily sedation interruption protocols are vital to assess neurological function and minimize prolonged use.

Consider glucose levels when administering, and be aware of potential interactions with vasopressors.

Antibiotic Stewardship

Prudent antibiotic use is crucial in critical care to combat rising antimicrobial resistance. Implement strategies like de-escalation based on culture results and limiting broad-spectrum agents.

Regularly review antibiotic prescriptions, considering patient-specific factors and local resistance patterns.

Prioritize source control and shorter durations when clinically appropriate, aligning with established guidelines to optimize patient outcomes and minimize collateral damage.

Infection Control Protocols

Rigorous hand hygiene, appropriate PPE utilization, and proactive prevention of CLABSI and VAP are essential for safeguarding vulnerable critical care patients.

Hand Hygiene and PPE

Consistent and meticulous hand hygiene remains the cornerstone of infection prevention in critical care settings. Healthcare professionals must adhere to the “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene” – before patient contact, before aseptic tasks, after body fluid exposure risk, after patient contact, and after patient environment contact.

Appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), including gloves, gowns, masks, and eye protection, forms a crucial barrier against transmission. Proper donning and doffing procedures are vital to prevent self-contamination and cross-contamination, safeguarding both patients and staff.

Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) Prevention

Preventing CLABSI requires a multifaceted approach centered on strict aseptic technique during central line insertion and maintenance. Maximal sterile barrier precautions – including sterile gown, gloves, mask, cap, and large sterile drape – are essential.

Daily review of line necessity, prompt removal when no longer indicated, and meticulous skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine are critical. Regular education and competency assessment of staff reinforce best practices, minimizing the risk of these potentially fatal infections.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) Prevention

VAP prevention hinges on minimizing intubation duration and elevating the head of the bed to 30-45 degrees to reduce aspiration risk. Daily sedation vacations and assessment of readiness to extubate are crucial.

Oral care with chlorhexidine, subglottic secretion drainage, and meticulous endotracheal tube cuff management are vital components. Strict hand hygiene and avoidance of unnecessary circuit changes further decrease the incidence of this serious hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Nutrition in the Critically Ill

Optimizing nutritional support—enteral or parenteral—is essential for recovery. Careful assessment guides individualized plans, supporting immune function and wound healing effectively.

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition, delivering nutrients directly to the gastrointestinal tract, is often the preferred method when feasible. It maintains gut integrity, reducing infection risks compared to parenteral routes. Careful consideration of the patient’s digestive capacity and tolerance is crucial.

Feeding tubes—nasogastric, nasojejunal, or gastrostomy/jejunostomy—facilitate delivery. Formulas are tailored to individual needs, considering illness severity and metabolic demands. Regular monitoring for complications like aspiration, diarrhea, and tube occlusion is paramount for successful implementation and patient safety.

Parenteral Nutrition

Parenteral nutrition (PN) provides nutrients intravenously, bypassing the digestive system, and is essential when the gut is non-functional. It requires meticulous formulation, including amino acids, dextrose, lipids, electrolytes, and vitamins, tailored to individual metabolic needs.

Central venous access is typically required for long-term PN. Close monitoring for complications—such as hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and catheter-related infections—is vital. PN should be transitioned to enteral nutrition as soon as the gut recovers, minimizing risks and promoting physiological function.

Nutritional Assessment

A comprehensive nutritional assessment is crucial in critical care, identifying patients at risk of malnutrition. This involves evaluating pre-existing nutritional status, illness severity, metabolic stress, and organ function.

Parameters include weight history, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin and prealbumin levels, and indirect calorimetry to determine energy expenditure. Accurate assessment guides appropriate nutritional support—enteral or parenteral—to optimize healing, immune function, and overall patient outcomes, acknowledging individual variations.

Renal Support in Critical Care

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common; renal replacement therapy (RRT) becomes vital when conservative measures fail to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

AKI frequently arises in critically ill patients due to hypoperfusion, nephrotoxic agents, or direct glomerular damage. Early identification, utilizing serum creatinine and urine output monitoring, is crucial.

Prompt intervention focuses on restoring hemodynamic stability and eliminating offending agents. However, when conservative strategies prove insufficient, renal replacement therapy—including hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy—becomes essential to manage fluid overload, electrolyte imbalances, and metabolic acidosis, ultimately improving patient survival.

Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)

RRT serves as a life-sustaining intervention when kidneys fail acutely. Hemodialysis efficiently removes solutes and excess fluid, typically employed for rapid correction of imbalances.

Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) offers gentler, slower fluid and solute removal, ideal for hemodynamically unstable patients. Selecting the appropriate modality depends on clinical context, considering patient stability and the severity of renal dysfunction. Careful monitoring of electrolytes and volume status is paramount during RRT.

Neurological Monitoring

Assessing neurological function via the Glasgow Coma Scale and pupillary response is crucial for detecting subtle changes and guiding critical interventions.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a standardized, objective assessment of a patient’s level of consciousness. It evaluates eye-opening response, verbal response, and motor response, each scored individually.

Scores range from 3 (completely unresponsive) to 15 (fully alert). Serial GCS assessments are vital for detecting neurological deterioration or improvement in critically ill patients.

Changes in GCS scores prompt further investigation, such as neuroimaging, and guide appropriate interventions to optimize cerebral perfusion and minimize secondary brain injury.

Pupillary Response

Assessing pupillary response is a crucial component of neurological examinations in critical care. Pupils should be equal in size, round, and reactive to light – constricting when stimulated and dilating in darkness.

Unequal pupil sizes (anisocoria), sluggish or absent responses, or fixed pupils can indicate increased intracranial pressure, brainstem dysfunction, or direct ocular injury.

Regular monitoring of pupillary response provides valuable insights into a patient’s neurological status and guides timely interventions to prevent further neurological damage.

Psychological Support for Patients and Families

Addressing anxiety and grief through open communication is vital; acknowledging emotional distress and providing compassionate support fosters resilience during critical illness.

Communication Strategies

Effective communication within the critical care setting necessitates clarity, empathy, and active listening. Regularly update families on the patient’s condition, utilizing non-technical language to ensure comprehension. Acknowledge their anxieties and provide honest, yet hopeful, assessments.

Establish a designated point of contact for consistent updates and encourage questions. Be mindful of cultural sensitivities and individual coping mechanisms. Open dialogue builds trust and facilitates shared decision-making, ultimately supporting both the patient and their loved ones through this challenging journey.

Addressing Anxiety and Grief

Anxiety and grief are common responses to critical illness. Acknowledge these emotions as valid and provide a safe space for expression. Offer emotional support through active listening and empathetic communication.

Facilitate access to chaplaincy services, social work, or psychological counseling. Normalize feelings of helplessness and uncertainty. Encourage family members to lean on their support systems. Remember, compassionate care extends beyond physical needs to encompass the emotional well-being of both patients and their families.

Ethical Considerations in Critical Care

Navigating end-of-life decisions and respecting advance directives are crucial; balancing patient autonomy with medical expertise demands thoughtful, compassionate, and legally sound approaches.

End-of-Life Care

Providing compassionate end-of-life care in critical care necessitates a holistic approach, acknowledging physical, emotional, and spiritual needs. Open communication with patients and families regarding prognosis and goals is paramount.

Respecting advance directives, including Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders, is ethically and legally essential. Pain and symptom management should prioritize comfort, and palliative care consultation can significantly enhance quality of life during this sensitive period.

Supporting grieving families and facilitating closure are integral components of ethical end-of-life practice, ensuring dignity and respect until the very end.

Advance Directives

Advance directives, encompassing living wills and durable powers of attorney for healthcare, articulate a patient’s wishes regarding medical treatment should they become incapacitated.

Critical care teams must proactively identify and honor these documents, ensuring patient autonomy is respected. Discussions about advance care planning should occur early and often, facilitating informed decision-making.

Legal and ethical frameworks mandate adherence to documented preferences, even if they differ from family desires, upholding the patient’s right to self-determination.

Common Critical Care Procedures

Central line and arterial line placements are frequent interventions; proficiency and meticulous technique are vital to minimize complications and ensure optimal patient monitoring.

Central Venous Catheter Insertion

Central venous catheter (CVC) insertion is a cornerstone procedure, demanding strict aseptic technique to prevent bloodstream infections (CLABSI). Proper site selection, utilizing anatomical landmarks and ultrasound guidance, is crucial for successful cannulation.

Meticulous attention to detail during catheter placement, including appropriate catheter size and securement, minimizes risks. Post-insertion care, diligent monitoring for complications like pneumothorax, and adherence to established protocols are essential for patient safety and positive outcomes.

Arterial Line Placement

Arterial line insertion provides continuous, real-time blood pressure monitoring and facilitates frequent blood gas analysis, vital for hemodynamic assessment. Radial artery access is preferred due to collateral circulation, but brachial or femoral sites may be necessary.

Successful placement requires anatomical knowledge, meticulous technique, and careful assessment of Allen’s test. Post-procedure monitoring for thrombosis, infection, and distal ischemia is paramount, ensuring optimal patient care and minimizing potential complications.

Discharge Planning and Follow-Up

Transitioning patients requires coordinated rehabilitation services and lower-level care planning, ensuring continuity and minimizing readmission risks for sustained recovery.

Transition to Lower Levels of Care

Successfully moving patients from the intensive environment necessitates a meticulously planned approach. This involves comprehensive assessments of functional status, medication reconciliation, and diligent coordination with receiving facilities – be it a step-down unit, skilled nursing facility, or the patient’s home.

Clear communication regarding the patient’s critical care course, ongoing needs, and potential complications is vital. A multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses, therapists, and social workers, collaborates to ensure a seamless and safe transfer, optimizing the patient’s continued recovery trajectory.

Rehabilitation Services

Early and aggressive rehabilitation is a cornerstone of recovery following critical illness. A tailored program, encompassing physical, occupational, and speech therapy, addresses impairments in strength, mobility, cognition, and communication.

These services aim to maximize functional independence, enabling patients to regain their ability to perform activities of daily living. Rehabilitation begins during the ICU stay with passive range of motion exercises and progresses as the patient’s condition improves, ultimately fostering a return to a meaningful quality of life.